By RICARDO ALONSO-ZALDIVAR

Twice now, abortion was almost a dealbreaker. This time, it was a dealmaker. But of hundreds of deals cut so health care legislation can stay alive, the hardest to keep may be the Senate's abortion compromise - achieved after 13 hours of negotiation. The volatile issue remains the biggest threat to getting a history-making bill to President Barack Obama.

Deals are the lifeblood of legislation. Mary Landrieu of Louisiana got $100 million more for her state, Connecticut's Joe Lieberman stripped the bill of a government insurance plan and Ben Nelson won a slew of favors for Nebraska - all in exchange for their votes.

Nelson was also pivotal in the abortion compromise. The abortion-rights foe cast the 60th vote Monday to prevent Republicans from burying the bill.

Abortion is an issue that doesn't usually lead to common ground, since interested groups have radically opposed views. That makes the Senate compromise - which seeks to prohibit the use of tax dollars for abortions - rare, even surprising. It's also why, as Senate Democrats move to negotiations with the House, other deals in their bill may stick more easily.

House liberals are starting to accept that they probably won't get a government insurance plan. But abortion opponents in the House nearly stopped health care once before, and they are poised to try again to preserve their more restrictive approach. It could be a dealbreaker.

Sen. Barbara Boxer, D-Calif., represented abortion rights supporters in the negotiations only to face criticism from women's rights groups, not just abortion opponents. Now, Boxer is urging lawmakers to take a second look. "You have both sides criticizing it, which means that we did what we had to do, we compromised in a fair way," Boxer said.

Hours before the Senate's abortion compromise came together last Friday, it looked like things would fall apart. Three Democratic officials familiar with the talks detailed how events unfolded. They spoke on condition of anonymity, because the talks were private.

Obama's health care remake extends coverage to 94 percent of Americans, not including illegal immigrants, and tries to slow increases in medical costs. But in the Senate, Nebraska's Nelson stood in the way. Among his chief objections was his belief that the Senate's restrictions on government funding for abortion were too lax.

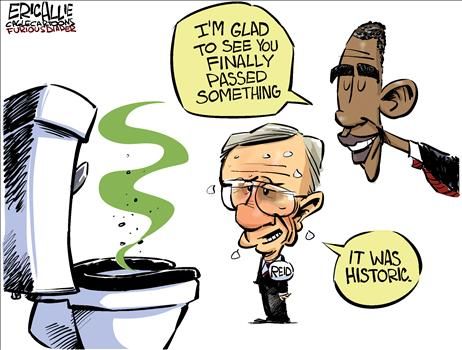

The negotiations began at 9:30 a.m. Friday in a suite of offices in the Capitol occupied by Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev. Steps from the Senate floor, Reid's spacious lair is shielded from inquisitive media. There would be suspense, shuttle diplomacy, hugs, and a call from Obama aboard Air Force One before the day was done.

Among those taking part were Reid, Nelson, Boxer, Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., and White House deputy chief of staff Jim Messina. Nelson and Boxer did not negotiate face-to-face but set up camp in different offices. Schumer, the No. 3 Senate Democrat, shuttled back and forth.

By the middle of the day, Nelson's home-state concerns had been addressed, and the focus turned to abortion. Federal law bans taxpayer funding of abortion, except in cases of rape, incest or to save the life of the mother. For months, the debate has been how to apply those principles to a new stream of federal subsidies under the health care bill. Senators had previously voted to reject Nelson's attempt to incorporate the more restrictive House language in the Senate bill.

Two alternatives were under discussion in Reid's office. Abortion opponents wanted no coverage in health plans receiving federal subsidies under the bill. Mirroring the House, women would have to buy a separate policy for abortion coverage. Abortion rights supporters wanted to allow plans to offer coverage, but individuals could opt out and get a partial rebate of their premiums. The two sides were deadlocked.

"I don't know how we'll ever solve this," Schumer said, according to one official who was present.

Then Nelson and one of his senior aides decided to try something different. States would be allowed to decide whether or not abortion could be covered by health plans operating in a new insurance marketplace under the bill. Plans covering abortion would have to collect a separate premium for the procedure, directly paid for by the person buying coverage. Premiums for abortion would be kept in a separate account.

Nelson believed it would solve the problem of segregating taxpayer funds from money for abortions. He told people he felt the discussion had degenerated to minutiae, so "we were arguing about a staple," said an official involved. Nelson meant it was acceptable to abortion opponents if supplemental abortion coverage was stapled to an insurance policy, but not if it was spelled out in the body of the policy itself.

By evening, the two sides took a break to consult with their respective constituencies. Nelson left Reid's suite, planning to return at 8:30 p.m. He called a leading anti-abortion activist in Nebraska, but was not able to get a commitment for the deal.

At 9:00 p.m. Nelson had yet to return. At 9:15, still no Nelson. Reid and Schumer started getting nervous. Finally, at 9:30, Nelson turned up. He and Boxer signed off on the deal within a half hour. Nelson came into Reid's office to say he'd hold off on a formal endorsement until the text of deal was released in the morning.

Reid and Nelson started to say goodnight, and wound up hugging each other. Nelson hugged Schumer next and then left.

Obama, aboard Air Force One on his way back from the climate summit in Copenhagen, called with congratulations. Reid put the president on speaker phone so Boxer and Schumer could hear.

After the deal became public Saturday, Nelson was slammed by former allies opposed to abortion. He tells people he feels like he's been bitten by the family dog.